Where does couscous grow?

If you bury a grain of couscous in wet soil, nothing will happen. No green shoot will show up, water or no water. There are no fields with lushly sprouting couscous, no plantations planted with couscous shrubs. And there are no ponds with emerald couscous shoots either. Because couscous is a man-made product made from ordinary semolina.

Cereal or pasta?

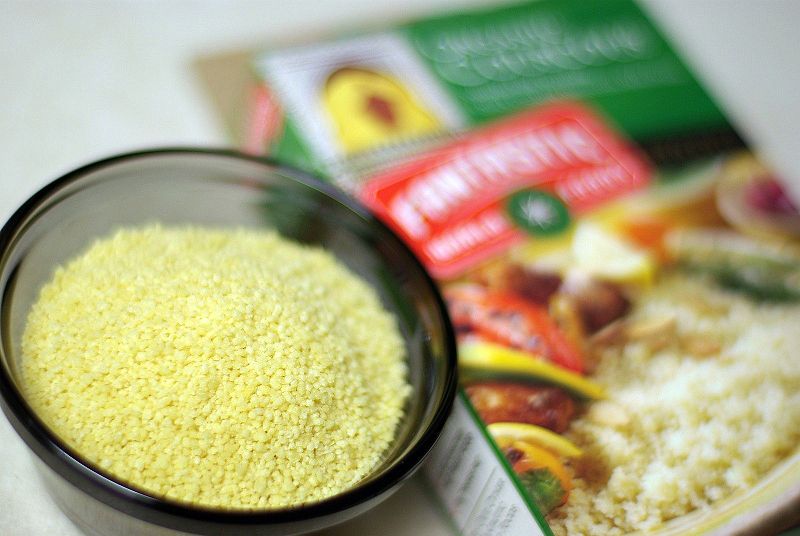

In its appearance couscous certainly resembles groats, and in stores small packages with light yellow balls can be found on the shelves with groats. But in terms of technology it is closer to pasta, for example to small Italian pasta orzo or Israeli ptitim.

Just like pasta, couscous is made from just two ingredients – durum wheat and water, only it requires coarsely ground grain, or semolina, rather than flour.

A small golden goose

In North Africa and the Middle East couscous is a matter of national pride. Some historical sources say that wheat semolina flour was introduced into Algeria during the Carthaginian period, which made it possible to invent couscous as early as the 2nd century B.C. Other historians say that couscous appeared much later, in the 13th century, under the influence of Andalusia.

Maybe the truth is somewhere in the middle, or maybe “calendars lie everything”, but couscous has more than passed the test of time and remains a favorite and everyday food of the inhabitants of the great Maghreb, and regardless of the social status of the eater. The differences are more evident in the second part of the dish, which can be prepared from very refined and expensive products as well as from the most accessible and simple.

Personal experience: from semolina to couscous

In order for semolina to be transformed into couscous, it is necessary to perform a number of seemingly simple operations. In order not to be unsubstantiated and not to describe someone else’s experience, I made couscous with my own hands. And for the sake of purity of the experiment, I decided to study both cooking methods that I know.

The first one, common in North African countries, required a tray with a concave bottom. In the absence of such a concave bottom, I used a large wok. I dusted it with flour, splashed it with water and added about a cup of semolina. Now I had to make a number of light rotating movements, as a result of which the semolina should form a layer of flour and take the form of small balls.

The experiment was disastrously unsuccessful. The result of all the spinning and shaking was a miserable handful, or rather, two dozen grits. And although these grains were quite plausible, the performance seemed to me useless. After all, they still had to be sifted for size, which clearly varied from very small grains of sand to overly coarse crumbs.

Apparently, to succeed in the venture, one had to be born a Tripolitan, mastering the skill at a genetic level, or at least spend some time in the society of strict Berber women sitting in a circle in a shady courtyard, meditatively, but deftly engaged in home preparation of their basic dish.

The second method, the Middle Eastern one, was much more effective. The flour poured into a bowl was to be salted, dripped with olive oil, moistened with a little warm water and kneaded while rolling small lumps with the palms of one hand. When the entire mass of “dough” took the desired lumpy form, it was necessary to squeeze it, again by hand, through a large-caliber, three- or even four-millimeter sieve.

Everything turned out great: I had a plate of neat, raw couscous in front of me. Now it had to be placed in another sieve, covered with gauze, and set, tightly capped, over the boiling water. Here the couscous was to spend the next half hour, then it had to be rubbed through the first sieve again, returned to the steamer and cook for another 30 minutes.

The whole process took more than 1.5 hours and fairly exhausted me. I respect tradition and honor culinary authenticity, but frankly, I am sincerely glad that the process of making couscous is now fully mechanized.

The 45-minute journey

Evaluating couscous not only as a worthy addition to the main dish, but also as the undoubted leader in cooking speed, it is impossible not to be happy that all stages of cooking couscous take place not in the home kitchen, but in a special shop.

The way this semolina begins from the tank, where it is mixed with water and moves further along the automatic line through numerous drums, sieves, steamers, rotating blades, cooling chambers and sieves again. After an intricate chain of operations in just 45 minutes, the semolina, finally transformed into couscous, is packaged in bags and ends up on store shelves.

Some manufacturers go further and enrich the product with various natural additives at the level of the last steps. So now it is quite possible to buy couscous with curry, with spinach, with tomato and basil. What’s more, there is couscous in small and medium so you can choose your own size.

The miracle of culinary simplicity.

The time it takes us to cook couscous depends directly on the amount of garnish we want. If we are talking about a large Arabic wedding, the obligatory couscous will be cooked in several voluminous couscousiere, or couscousiere – special devices that are a two-story saucepan of considerable size.

Meat or poultry with coarsely chopped vegetables and spicy herbs is put in the lower part of the pot, salted and generously spiced. Over this source of steam, filled with all the aromas of the East, is the second part of the couscous pan – a pot with a perforated bottom, a steam cooker, in which couscous will be poured. Covered with a lid it will be steaming, saturated with the fragrance of herbs and spices, becoming light and crumbly, for at least 2-3 hours.

There may be a completely different situation, probably familiar to everyone, including even perfectly collected and not desperate hostesses, when there is not much time left for cooking. And then our salvation is couscous in any of its variations, such as with roasted peppers, cilantro and fresh tomato, which can be made in just 20 minutes.

However, no matter how many times you say the word “halva,” it won’t get sweet. Same with couscous – better to cook it and make your own opinion.